|

|

| (Nie pokazano 64 wersji utworzonych przez 4 użytkowników) |

| Linia 1: |

Linia 1: |

| | {{DISPLAYTITLE:''Saurolophus''}} | | {{DISPLAYTITLE:''Saurolophus''}} |

| − | To jest wstępna wersja artykułu.

| |

| | <small> | | <small> |

| | {| class="wikitable" style="background-color:CornSilk" | | {| class="wikitable" style="background-color:CornSilk" |

| Linia 24: |

Linia 23: |

| | <small>(formacja [[Horseshoe Canyon]]; Alberta)</small> <br> | | <small>(formacja [[Horseshoe Canyon]]; Alberta)</small> <br> |

| | [[Mongolia]]<br> | | [[Mongolia]]<br> |

| − | <small>(formacja [[Nemegt]]; prowincja [[Omnogov]])</small> <br> | + | <small>(formacja [[Nemegt]]; prowincja Omnogov)</small> <br> |

| − | [[USA]]<br>

| |

| − | <small>(formacja [[Kirtland]]; stan [[Nowy Meksyk]])</small><br>

| |

| | [[Chiny]]<br> | | [[Chiny]]<br> |

| | <small>(Beiliyie Kruchi; Heilungchiang)</small> | | <small>(Beiliyie Kruchi; Heilungchiang)</small> |

| | |- | | |- |

| | ! '''[[:Kategoria:Czas|Czas występowania]]''' | | ! '''[[:Kategoria:Czas|Czas występowania]]''' |

| − | | 83,5-65,5 [[Ma]] | + | |{{Występowanie|83.5|66}} |

| − | | + | 83,5-66 [[Ma]]<br> |

| | <small>późna [[kreda]] ([[kampan]]-[[mastrycht]])</small> | | <small>późna [[kreda]] ([[kampan]]-[[mastrycht]])</small> |

| | |- | | |- |

| Linia 47: |

Linia 44: |

| | | | |

| | [[Saurolophinae]] | | [[Saurolophinae]] |

| | + | |

| | + | [[Saurolophini]] |

| | |- | | |- |

| | | colspan=2 |[[Plik:Saurolophus.png|400px]] | | | colspan=2 |[[Plik:Saurolophus.png|400px]] |

| Linia 55: |

Linia 54: |

| | |- | | |- |

| | | colspan=2 | | | | colspan=2 | |

| − | <display_points type="terrain" zoom=3> | + | <display_points type="terrain" zoom=2> |

| − | 51.8° N, 113.0° W|[[Red Deer River]], [[Edmonton]], [[Kanada]]|<small>''[[Saurolophus]] osborni'' - '''AMNH 5220''' ([[holotyp]]) i AMNH 5221 z 1911 r.<br> | + | 51.8° N, 113.0° W~[[Red Deer River]], [[Edmonton]], [[Kanada]]~''[[Saurolophus]] osborni'' - '''AMNH 5220''' ([[holotyp]]) i AMNH 5221 z 1911 r.<br> |

| | </display_points> | | </display_points> |

| | <small>Mapa 1. Występowanie ''Saurolophus osborni''.</small><hr> | | <small>Mapa 1. Występowanie ''Saurolophus osborni''.</small><hr> |

| − | <display_points type="terrain" zoom=3> | + | <display_points type="terrain" zoom=2> |

| − | 43.5° N, 101.3° E|formacja [[Nemegt]]|<small>''[[Saurolophus]] angustirostris'' - '''PIN 551-8''' - [[holotyp]] z 1948-1949 r.<br> ''[[Saurolophus]] angustirostris'' - 12 okazów z 1964-1970 r.</small> | + | 43.5° N, 101.3° E~formacja [[Nemegt]]~''[[Saurolophus]] angustirostris'' - '''PIN 551-8''' - [[holotyp]] z 1948-1949 r.<br> ''[[Saurolophus]] angustirostris'' - 12 okazów z 1964-1970 r. |

| − | 43.6° N, 100.5° E|[[Altan Ula]] III-IV, formacja [[Nemegt]]|<small>''[[Saurolophus]] angustirostris'' - 1 okaz z 1970-1971 r.</small> | + | 43.6° N, 100.5° E~[[Altan Ula]] III-IV, formacja [[Nemegt]]~''[[Saurolophus]] angustirostris'' - 1 okaz z 1970-1971 r.</small> |

| − | 44° N, 120° E|Beilyie Kruchi, Heilungchiang|<small>''[[Saurolophus]] kryschtofovici ([[nomen dubium]])'' - fragment kości kulszowej.</small> | + | 44° N, 120° E~Beilyie Kruchi, Heilungchiang~''[[Saurolophus]] kryschtofovici'' |

| | </display_points> | | </display_points> |

| | <small>Mapa 2. Występowanie ''Saurolophus angustirostris'' i ''S. kryschtofovici''.</small><hr> | | <small>Mapa 2. Występowanie ''Saurolophus angustirostris'' i ''S. kryschtofovici''.</small><hr> |

| − | <display_points type="terrain" zoom=1>

| |

| − | 43.9° N, 100.1° E|[[Gurlin Tsav]], formacja [[Nemegt]]|<small>''[[Saurolophus]]'' sp. - ok. 300 tropów</small>

| |

| − | 43.8° N, 100.0° E|[[Bugin Tsav]], formacja [[Nemegt]]|<small>''[[Saurolophus]]'' sp. - 1 okaz z 1993-1995 r.; 10 tropów</small>

| |

| − | 36.2° N, 107.9° W|[[San Juan]], formacja [[Kritland]]|<small>''? [[Saurolophus]]'' sp. - z 1916 r.</small>

| |

| − | 41.9° N, 109.1° W|[[Sweetwater]], formacja [[Almond]]|<small>''[[Saurolophus]]'' sp. - z 1937 r.</small>

| |

| − | 53.4° N, 113.5° W|formacja [[Horseshoe Canyon]]|<small>''[[Saurolophus]]'' sp.</small>

| |

| − | </display_points><small>Mapa 3. Występowanie ''Saurolophus'' [[sp.]]</small>

| |

| | |} | | |} |

| | | | |

| | ==Wstęp== | | ==Wstęp== |

| | + | '''Zaurolof''' (''Saurolophus'') to [[rodzaj]] późnokredowego, szeroko rozpowszechnionego [[Hadrosauridae|hadrozauryda]], którego liczne szczątki znane są z [[Ameryka Północna|Ameryki Północnej]] i [[Azja|Azji]]. Ten roślinożerny dinozaur wyróżniał się charakterystycznym wyrostkiem na czaszce, tworzonym przez przedłużenie kości nosowej, a sięgającym aż za krawędź czaszki. |

| | | | |

| − | ==''Saurolophus osborni''== | + | =='''''Saurolophus osborni'''''== |

| − | | + | [[Plik:Saurolophus osborni in situ.jpg|300px|thumb|right| Ryc. 2. Szkielet holotypowy zaurolofa w trakcie wydobywania ze skał (rok 1911). Okaz leży na prawym boku, czaszka jest otoczona piaskowcem z [[ripplemarki|ripplemarkami]] (zmarszczkami), po lewej stronie znajduje się kręgosłup, zaś ogon rozciąga się aż do miejsca, w którym pracuje naukowiec. <br><br> |

| | + | © Brown, 1913]] |

| | + | [[Plik:Saurolophus osborni czaszka.jpg|300px|thumb|right| Ryc. 3. Czaszka ''S. osborni'' {{Kpt|Brown, 1912}} z ułamanym wyrostkiem naczaszkowym ("grzebieniem"). |

| | + | <br><br> |

| | + | © Brown, 1912]] |

| | + | [[Plik:Saurolophus osborni holotyp.jpg|300px|thumb|right| Ryc. 4. Holotyp ''S. osborni'' {{Kpt|Brown, 1912}} z ułamanym wyrostkiem naczaszkowym ("grzebieniem"). |

| | + | <br><br> |

| | + | © Brown, 1912]] |

| | ===Historia odkrycia=== | | ===Historia odkrycia=== |

| | + | W 1911 roku w trakcie wykopalisk prowadzonych na terenie formacji [[Horseshoe Canyon]] (wówczas nazywana formacją [[Edmonton]]) w stanie Alberta w Kanadzie (patrz: mapa 1) zespół naukowców z Amerykańskiego Muzeum Historii Naturalnej, z paleontologiem [[Barnum Brown|Barnumem Brownem]] na czele, odkrył wspaniale zachowany, [[artykulacja|artykułowany]] szkielet zaurolofa, któremu nadany został numer katalogowy AMNH 5220 (ryc. 2, 4). Nieopodal tego samego miejsca odnaleziono również nieartykułowaną czaszkę (AMNH 5221), która została później ustanowiona [[paratyp]]em<ref name="Glut97"></ref> oraz fragment kości kulszowej (AMNH 5225), błędnie przypisanej jako [[plezjotyp]] (więcej o AMNH 5225 w rozdziale [[#Historia_AMNH_5225|"Historia AMNH 5225"]]). |

| | | | |

| | ===Materiał kopalny=== | | ===Materiał kopalny=== |

| | + | [[Holotyp]]: AMNH 5220 - [[artykulacja|artykułowany]], niemal kompletny szkielet (m.in. brak dystalnego końca kości kulszowej), z zachowanymi odciskami skóry (ryc. 2,3,4) |

| | + | |

| | + | [[Paratyp]]: AMNH 5221 - nieartykułowana czaszka. |

| | + | |

| | + | [[Plezjotyp]]: AMNH 5225 - kompletna kość kulszowa (więcej o AMNH 5225 w rozdziale [[#Historia_AMNH_5225|"Historia AMNH 5225"]]). |

| | | | |

| | ===Diagnoza=== | | ===Diagnoza=== |

| | + | {{Szablon:Diagnoza}} |

| | + | |

| | + | Kości nosowe wydłużone tylno-grzbietowo ponad dach czaszki, tworząc lity, podobny do pręta wyrostek, współtworzony przez k. przedczołowe i czołowe; okołonozdrzowa struktura rozciąga się tylno-grzbietowo ponad całkowitą długość dachu czaszki (u osobników dorosłych) na grzbietowej powierzchni k. nosowej ([[konwergencja]] u ''[[Brachylophosaurus]] canadensis''); trzyczęściowa k. czołowa składająca się z: części głównej - dachu przedniej części puszki mózgowej, przedniowewnętrznie pochyłej półki (konwergencja u niektórych lambeozaurynów) i skierowanej tylno-grzbietowo, palcowatej gałęzi, podpierającej spodnią część grzebienia naczaszkowego; k. przedczołowa z wydłużonym tylnogrzbietowo wyrostkiem, wspierającym bocznie grzebień; tylnogrzbietowe wyrostki k. czołowej i przedczołowej złączone, tworzą grzbietowy wzgórek (''promontorium''), który podpiera od spodu grzebień naczaszkowy (konwergencja u niektórych lambeozaurynów); przednie zagłębienie i stromy spadek grzebienia ciemieniowego u osobników dorosłych (konwergencja u Lambeosaurinae); dwa ponadoczodołowe elementy obecne pomiędzy k. przedczołową i zaoczodołową; k. ciemieniowa wyłączona z tylnogrzbietowej krawędzi potylicy przez staw międzyłuskowy (konwergencja u ''[[Maiasaura]] peeblesorum'', ''[[Shantungosaurus]] giganteus'' i licznych lambeozaurynów)<ref>p-m,2012</ref>,<ref>wagner2010</ref><ref>bell,2010</ref>. |

| | + | |

| | + | Kośći - promieniowa i barkowa podobnej długości; 8 kręgów krzyżowych; kość kulszowa bez wznoszącej się "stopy" (wbrew danym z oryginalnego opisu z 1912); kość łonowa z krótkim, wznoszącym się ku przodowi ostrzem; k. biodrowa silnie łukowata, przedni wyrostek zakrzywiający się w dół, cienki płat pionowy; czwarty krętarz k. udowej znajdujący się poniżej połowy kości; palce II i IV krótkie<ref name="Bro1912"></ref>. |

| | + | |

| | + | [[Pierścień sklerotyczny]] z czaszki holotypowej wskazuje, że oko było znacznie mniejsze niż oczodół. W 1940 roku [[Loris Russell]] wykazał, że poszczególne płytki pierścienia nie są ustawione szeregowo, zachodząc na siebie w jednym kierunku, ale raczej występuje jeden lub więcej segmentów, w których kierunek nachodzenia na siebie płytek jest odwrotny niż w pozostałej części pierścienia<ref name="Russell40">Russell, L.S., 1940. "The sclerotic ring in the Hadrosauridae". Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada. 11 pp.</ref>. |

| | | | |

| | ===Etymologia=== | | ===Etymologia=== |

| Linia 88: |

Linia 101: |

| | Nazwa [[rodzaj]]owa ''Saurolophus'' oznacza "grzebieniasty jaszczur" (z greckiego ''sauros'' - jaszczur i ''lophus'' - grzebień)<ref name="Bro1912">Barnum Brown, 1912. A crested dinosaur from the Edmonton Cretaceous. ''Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History'' '''31''' (14): 131–136.</ref>. Epitet [[gatunek|gatunkowy]] - ''osborni'' - honoruje zasłużonego amerykańskiego paleontologa - [[Henry Fairfield Osborn|Henry'ego Fairfielda Osborna]]. | | Nazwa [[rodzaj]]owa ''Saurolophus'' oznacza "grzebieniasty jaszczur" (z greckiego ''sauros'' - jaszczur i ''lophus'' - grzebień)<ref name="Bro1912">Barnum Brown, 1912. A crested dinosaur from the Edmonton Cretaceous. ''Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History'' '''31''' (14): 131–136.</ref>. Epitet [[gatunek|gatunkowy]] - ''osborni'' - honoruje zasłużonego amerykańskiego paleontologa - [[Henry Fairfield Osborn|Henry'ego Fairfielda Osborna]]. |

| | | | |

| − | ==''S. angustirostris''== | + | =='''''S. angustirostris'''''== |

| | + | [[Plik:Saurolophus angustirostris1.jpg|300px|thumb|right| Ryc. 5. Czaszka ''S. angustirostris'']] |

| | + | ===Historia odkryć=== |

| | + | W roku 1948 ekipa paleontologów z [[Radziecko-Mongolskie Ekspedycje Paleontologiczne|Radziecko-Mongolskich Ekspedycji Paleontologicznych]] odkryła w skałach twardego, czerwonego piaskowca Altan Ula (pustynia Gobi; [[Mongolia]]) siedem dużych szkieletów hadrozaurów, wraz z odciskami skóry. Ze względu na bliskie sąsiedztwo poszczególnych okazów, miejsce zostało nazwane "Grobowcem Smoka" (''"Dragons' Tomb"''). Znalezione skamieniałości zostały przypisane do nowego gatunku - ''Saurolophus angustirostris''<ref>Michael Novacek, Dinosaurs of Falming Cliffs, 1997. p. 131-132</ref>. |

| | | | |

| − | ===Historia odkryć===

| + | Również w trakcie trwania późniejszych [[Polsko-Mongolskie Ekspedycje Paleontologiczne|Polsko-Mongolskich Ekspedycji Paleontologicznych]] odkrywano liczne okazy azjatyckiego zaurolofa, w tym jeden, szacowany na 12 metrów długości, odkryty przez Ryszarda Gradzińskiego, Józefa Kaźmierczaka i Jerzego Lefelda<ref>K-J, Polowanie na d.</ref>. |

| | | | |

| | ===Materiał kopalny=== | | ===Materiał kopalny=== |

| | + | [[Holotyp]]: PIN 551-8 - niemal kompletny szkielet z "Grobowca Smoka". |

| | + | |

| | + | Znanych jest około 20 mniej lub bardziej kompletnych szkieletów zaurolofa i ogromną ilość nieartykułowanych kości. Dzięki powszechności szczątków tego zwierzęcia, można zrekonstruować jego ontogenezę; najmniejszym osobnikiem jest okaz ZPAL MgD−1/159 (czaszka i fragment szkieletu niedojrzałego zaurolofa), zaś największym - PIN 551/357 (fragmentaryczna czaszka sędziwego zwierzęcia) lub PIN 551/356 (błędnie podawany jako 662/2 lub 552/2 w publikacji<ref>Słowiak, J., Szczygielski, T., Ginter, M., Fostowicz‐Frelik, Ł. 2020. Uninterrupted growth in a non‐polar hadrosaur explains the gigantism among duck‐billed dinosaurs. Palaeontology, w druku. [https://doi.org/10.1111/pala.12473]</ref>, Słowiak inf. ustna). |

| | | | |

| | ===Diagnoza=== | | ===Diagnoza=== |

| | + | Czaszka węższa od ''S. osborni'', grzebień naczaszkowy dłuższy<ref name="Roz52"></ref>; nozdrza krótsze; kość łzowa krótsza i głębsza; wyrostek żuchwy wydłużony, wchodzi klinem między k. szczękową i łzową<ref>Mary&Osmólska, 81a</ref>. |

| | | | |

| | ===Porównanie z ''S. osborni''=== | | ===Porównanie z ''S. osborni''=== |

| | + | {{Szablon:Diagnoza}} |

| | + | ====Czaszka==== |

| | + | Maryańska i Osmólska w 1984<ref>M&O84</ref> roku wykazały 8 cech czaszki, które miały odróżniać mongolski i kanadyjski gatunek zaurolofa; w 2000 roku Norman i Sues<ref>N&S,2000</ref> stwierdzili jednak, że te cechy diagnostyczne mogą być wyrazem zmienności osobniczej. Horner w 1992<ref>Horner, 1992</ref> postulował, by za cechę rozróżniającą uznać "podporę czołową" (ang. "''frontal buttress''") - czyli wyrostek tylnogrzbietowy (''posterodorsal process''), obecny tylko u ''S. angustirostris'', a obecnie uznawany za synapomorfię tego gatunku<ref>Bell, 2011</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | ===Tropy===

| + | Mongolski gatunek ma również czaszkę co najmniej o 20% dłuższą od kanadyjskiego krewniaka; kość przedszczękowa ma silnie zaznaczoną krawędź oralną i podwinięte ciało przedszczękowe w widoku bocznym; szeroko łukowatą przednią krawędź dołu przednozdrzowego; wydłużoną, skierowaną ku przodowi "ostrogę" na przednim wyrostku k. jarzmowej, oddzielającą k. łzową i k. szczękową, bardziej niż u ''S. osborni''; płytkie nacięcie kwadratowo-jarzmowe na k. kwadratowej; silniej pochylona k. kwadratowa w widoku bocznym<ref>Bell, 2011</ref>. |

| | | | |

| − | ===Etymologia=== | + | ====Skóra==== |

| | | | |

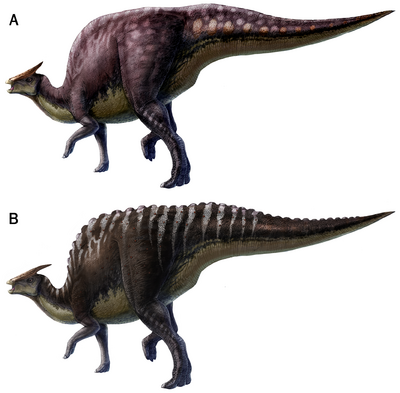

| − | Jak podaje [[Anatoly Konstantinovich Rozhdestvensky]] w oryginalnej, rosyjskiej publikacji z 1952 roku, ''S. angustirostris'' oznacza "зауролоф узкомордый", czyli "wąskopyski zaurolof"<ref name="Roz52">Рождественский, A.K. 1952. Новый представитель утконосых динозавров из Верхнемеловых отложений монголии. ''Доклады Академии Наук СССР'' '''86''': 405-408. <br>[Rozhdestvensky, A.K. 1952. A new representative of the duck-billed dinosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous deposits of Mongolia. ''Doklady Akademii Nauk S.S.S.R.'' '''86''': 405–408.]</ref>.

| + | W 2012 roku kanadyjski paleontolog, [[Phill Bell|Phill R. Bell]] z Wydziału Nauk Biologicznych Uniwersytetu Alberta, opublikował badania dotyczące porównania odcisków skóry ''S. angustirostris'', pochodzących z kolekcji znajdujących się na całym świecie (kilka okazów należących do tego gatunku zostało udostępnionych przez Magdalenę Borsuk-Białynicką ze zbiorów Instytutu Paleobiologii PAN) i o wiele rzadszych, przypisanych do ''S. osborni'' (odciski z okolicy szczęk, miednicy, stopy i ogonana; które odnalezione zostały wraz z holotypem i paratypem, ale nie zostały uwzględnione w oryginalnej publikacji)<ref>Bell,2012</ref>. Badania wykazały, że te dobrze zbadane pod względem osteologicznym taksony, mogą być rozróżniane w oparciu o anatomię tkanek miękkich - różnice są bowiem widoczne w kształcie i układzie łusek. Najbardziej spektakularne są odmienności w układzie łusek na ogonie – u mongolskiego gatunku obecne są pionowe pasma wyraźnych łusek i płaskie, sporej wielkości guzki biegnące wzdłuż linii środkwoej grzbietu. Jak wynika z badań, architektura łusek jest zgodna w każdym stadium ontogenetycznym ''S. angustirostris'', dzięki czemu potwierdza się wcześniejsza hipoteza, iż układ tych struktur jest charakterystyczny dla danego taksonu. Co więcej, uważa się, że układ łusek może w pewnym stopniu wpływać na ubarwienie zwierzęcia – być może ''S. osborni'' był cętkowany, a ''S. angustitrostris'' posiadał pasy (ryc. 1). |

| | | | |

| − | ==''S. morrisi''== | + | ===Tropy=== |

| | + | w 1999 japoński paleontolog Shinobu Ishigaki doniósł o odkryciu ponad 600 dużych (25-155 cm długości), trójpalczastych tropów z późnej kredy w stanowiskach Bugeen Tsav i Gurilin Tsav w zachodniej części pustyni Gobi. Ichnoskamieniałości te zostały zebrane w latach 1995-1998 przez zespół łączonej ekspedycji Muzeum Nauk Przyrodniczych w Hayshsibara i Mongolskiego Centrum Paleontologicznego. Tropy, niechybnie należące do sporego ornitopoda, zostały przypisane do zaurolofa, w oparciu o powszechność występowania tego rodzaju na tym terenie, w tym samym czasie. Poza tropami zaurolofów, Japońsko-Mongolska ekspedycja zebrała ponad 15 000 tropów - również należących do ankylozaurydów i teropodów<ref name>Ishigaki,S., 1999. Abundant Dinosaur Footprints from Upper Cretaceous of Gobi Desert, Mongolia. ''Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology'' '''19''', Supplement to Number 3, 54A.</ref>. |

| | | | |

| − | ===Historia odkrycia=== | + | ===Etymologia=== |

| | | | |

| − | ===Materiał kopalny===

| + | Jak podaje [[Anatoly Rozhdestvensky]] w oryginalnej, rosyjskiej publikacji z 1952 roku, ''S. angustirostris'' oznacza "зауролоф узкомордый", czyli "wąskopyski zaurolof"<ref name="Roz52">Рождественский, A.K. 1952. Новый представитель утконосых динозавров из Верхнемеловых отложений монголии. ''Доклады Академии Наук СССР'' '''86''': 405-408. <br>[Rozhdestvensky, A.K. 1952. A new representative of the duck-billed dinosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous deposits of Mongolia. ''Doklady Akademii Nauk S.S.S.R.'' '''86''': 405–408.]</ref>. |

| − | | |

| − | ===Diagnoza===

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Etymologia===

| |

| − | ''S. morrisi'' honoruje paleontologa [[William J. Morris|Williama J. Morrisa]], który wsławił się badaniami nad morfologią funkcjonalną i historią ewolucyjną hadrozaurydów z wybrzeża Pacyfiku i Środkowego Zachodu Ameryki Północnej<ref name="PM12">Prieto-Márquez, A., Wagner, J.R. 2012. ''Saurolophus morrisi'', a new species of hadrosaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of the Pacific coast of North America. ''[[Acta Palaeontologica Polonica]] (w druku)''</ref>. | |

| | | | |

| | ==''S. kryschtofovici''== | | ==''S. kryschtofovici''== |

| Linia 120: |

Linia 139: |

| | © Riabinin, 1930]] | | © Riabinin, 1930]] |

| | | | |

| − | W 1930 roku rosyjski paleontolog, [[Anatoly Nikolaevich Riabinin]] opisał fragment lewej kości kulszowej (dokładnie jej bliższy koniec; ryc. XX) jako nowy gatunek zaurolofa - ''S. kryschtofovici'' (najprawdopodobniej na cześć kogoś o nazwisku Kryschtofovic). Skamieniałość została znaleziona w Beilyie Kruchi, na północy Heilungchiang w [[Chiny|Chinach]]<ref name="Ria30">Riabinin, A.N. 1930. On the age and fauna of the dinosaur beds on the Amur River. ''Mémoir, Société Mineral Russia'' '''59''': 41–51.</ref>. Obecnie gatunek ten jest uznawany za ''[[nomen dubium]]'' i zazwyczaj łączony z ''S. angustitornis'', m.in. ze względu na bliskość ich występowania (patrz: Mapa 2)<ref name="Glut97">Glut, D.F. 1997. ''Saurolophus''. "Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia". McFarland & Co. pp. 788–789.</ref>. | + | W 1930 roku rosyjski paleontolog, [[Anatoly Riabinin]] opisał fragment lewej kości kulszowej (dokładnie jej bliższy koniec; ryc. XX) jako nowy gatunek zaurolofa - ''S. kryschtofovici'' (najprawdopodobniej na cześć kogoś o nazwisku Kryschtofovic). Skamieniałość została znaleziona w Beilyie Kruchi, na północy Heilungchiang w [[Chiny|Chinach]]<ref name="Ria30">Riabinin, A.N. 1930. On the age and fauna of the dinosaur beds on the Amur River. ''Mémoir, Société Mineral Russia'' '''59''': 41–51.</ref>. Obecnie gatunek ten jest uznawany za ''[[nomen dubium]]'' i zazwyczaj łączony z ''S. angustitornis'', m.in. ze względu na bliskość ich występowania (patrz: Mapa 2)<ref name="Glut97">Glut, D.F. 1997. ''Saurolophus''. "Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia". McFarland & Co. pp. 788–789.</ref>. |

| | + | |

| | + | Ze względu na to, że w 1930 roku znany był tylko jeden, amerykański gatunek zaurolofa, do którego przypisana została kość kulszowa najprawdopodobniej innego dinozaura (więcej w rozdziale "[[Saurolophus#Historia_AMNH_5225|Historia AMNH 5225]]"), dystalny fragment holotypu ''S. kryschtofovici'' został zrekonstruowany z charakterystyczną, wzniesioną "stopą" na wierzchołku (w literaturze naukowej mowa wówczas o ''ischium'' typu "''footed''"). Obecnie wiadomo, że wszystkie gatunki zaurolofa miały delikatnie zakończoną kość kulszową (ryc. YY). |

| | + | |

| | + | ==Klasyfikacja== |

| | + | {{Drzewo}} |

| | + | {{klad| style=font-size:90%; line-height:100% |

| | + | |label1='''[[Saurolophini]]''' |

| | + | |1={{klad |

| | + | |1=''[[Prosaurolophus]] maximus'' |

| | + | |2={{klad |

| | + | |1=''[[Augustynolophus]] morrisi'' |

| | + | |2={{klad |

| | + | |1=''[[Saurolophus]] [[Saurolophus#Saurolophus_osborni|osborni]]'' |

| | + | |2=''[[Saurolophus]] [[Saurolophus#S._angustirostris|angustirostris]]'' |

| | + | }} |

| | + | }} |

| | + | }} |

| | + | }} |

| | + | [[Kladogram]] ukazujący relacje ''[[Saurolophus]]'' w obrębie [[Saurolophini]] (za: Prieto-Márquez ''et al.'', 2014.<ref name="PM2014">Augustynolophus</ref>). |

| | + | |

| | | | |

| | ==Spis gatunków== | | ==Spis gatunków== |

| | {| class="wikitable" | | {| class="wikitable" |

| | ! ''Saurolophus'' | | ! ''Saurolophus'' |

| − | | {{Kpt|[[Brown]]}}, [[1912]] | + | | {{Kpt|[[Barnum Brown|Brown]]}}, [[1912]] |

| | |- | | |- |

| | ! ''S. osborni'' | | ! ''S. osborni'' |

| − | | {{Kpt|[[Brown]]}}, [[1912]] | + | | {{Kpt|Brown}}, 1912 |

| | |- | | |- |

| | ! ''S. angustirostris'' | | ! ''S. angustirostris'' |

| − | | {{Kpt|[[Rozhdestvensky]]}}, [[1952]] | + | | {{Kpt|[[Anatoly Rozhdestvensky|Rozhdestvensky]]}}, [[1952]] |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | ! ''S. morrisi''

| + | | ''S. morrisi'' |

| − | | {{Kpt|[[Prieto-Márquez]]}} i {{Kpt|[[Wagner]]}}, [[2012]] | + | | {{Kpt|[[Albert Prieto-Márquez|Prieto-Márquez]], [[Jonathan Wagner|Wagner]]}}, [[2013]] |

| | + | | = ''[[Augustynolophus]] morrisi'' |

| | |- | | |- |

| | | ''S. kryschtofovici'' | | | ''S. kryschtofovici'' |

| − | | {{Kpt|[[Riabinin]]}}, [[1930]] | + | | {{Kpt|[[Anatoly Riabinin|Riabinin]]}}, [[1930]] |

| | | ''[[nomen dubium]]'' | | | ''[[nomen dubium]]'' |

| | + | | ?= ''S. angustirostris'' |

| | |} | | |} |

| | | | |

| Linia 153: |

Linia 194: |

| | [[Kategoria:Chiny]] | | [[Kategoria:Chiny]] |

| | [[Kategoria:Ameryka Północna]] | | [[Kategoria:Ameryka Północna]] |

| − | [[Kategoria:USA]]

| |

| | [[Kategoria:Kanada]] | | [[Kategoria:Kanada]] |

| | [[Kategoria:Mezozoik]] | | [[Kategoria:Mezozoik]] |

| Linia 159: |

Linia 199: |

| | [[Kategoria:Kampan]] | | [[Kategoria:Kampan]] |

| | [[Kategoria:Mastrycht]] | | [[Kategoria:Mastrycht]] |

| − | | + | [[Kategoria:Rodzaj wielogatunkowy]] |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Glut 1997

| |

| − | | |

| − | Znane z lokacji: formacja Horseshoe Canyon (Alberta, Kanada)

| |

| − | formacja Nemegt (Omnogov; Mongolia)

| |

| − | neinazwana formacja w Heilungchang, Chiny

| |

| − | | |

| − | znany materiał: 18 okazów (1997), kompletny szkielet, dwie kompletne izolowane czaszki, zarówno dojrzałych jak i młodocianych (juwenilnych) osobników.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Holotyp: AMNH 5220, niemal kompletny szkielet z odcisiem skóry

| |

| − | Paratyp: AMNH 5221 - nieartykułowana czaszka

| |

| − | Plezjotyp: AMNH 5225 - kompletna k. kulszowa

| |

| − | | |

| − | Diagnoza:

| |

| − | S. osborni (Brown 1912b)

| |

| − | czaszka z długim, tylnim kostnym grzebieniem tworzonym przez wydlużenie kosci czołowej i nosowej;

| |

| − | k. lzowa bardzo długa, wyższy wyroste k. przedszczękowej wznosi się do tylnej granicy nozdrzy

| |

| − | promieniowa i barkowa podobnej długości

| |

| − | 8 kręgów krzyżowych

| |

| − | kulszowa kończy się wznosząca "stopa"

| |

| − | łonowa z któtkim wznoszącym się przednio ostrzem

| |

| − | biodrowa silnie łukowata, przedni wyrostek zakrzywiony w dół, cienki płat

| |

| − | czwarty krętarz k. udowej poniżej połowy trzony

| |

| − | palce II i IV krótie

| |

| − | | |

| − | S. angustirostris

| |

| − | -węzsza czaszka i dłuższy grzebień (Rozhdestevensky 1957)

| |

| − | Maryańska & Osmólska 1981a:

| |

| − | -krósze nozdrza

| |

| − | -krótsza i głębsza k. łzowa

| |

| − | -przednia część żuchwy wydłużona w długi wyrostek, wchodzący klinem między k. szczękową i łzową

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Saurolophus to pierwszy kanadjski dinozaur znany z niemal kompletnego szkieletu.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Historia odkrycia:

| |

| − | 1911 - Amerykańskie Muzeum historii naturalnej z Horseshoe Canyon Formation, wówczas znane jako formacja Edmonton.

| |

| − | 1912 - Barnum Brown opisuje holotyp i czasszkę; szkielet zostaje wypreparowany i wystawiony w amerykańskim muzeum historii naturalnej

| |

| − | 1913 - Barnum Brown opisuje Saurolophus osborni.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Saurolophus to duzy hadrozaur = holotypowysz szkielet mierzył ok. 8,4 m; 2 tony (Paul, 1988 - Glut, 1997)

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Najbardziej wyróżniającą się cechą zaurolofa był kostny grzebień, który wznosi się ponad kąt czaszki niczym kolec. Brown 1912b,1913a porównywał grzebień do tego, ubecnego u kameleona, sugerując, że służył on do jako miejsce przyczepu silnych mięśni.

| |

| − | Dodson 1975 - sugeruje, że grzebienie mogły mieć znaczenie w identyfikacji płciowej.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Pierścień sklerotyczny z holotypowej czaszki wykazuje, że oko było znacznie mniejsze niż oczodół. Ruszeel 1940a wykazal, że płyty pierścienia sklerotycznego nie są szeregowe w jednym kierunku, ale raczej mają jeden lub więcej segmentów w których płytki nachodzą na siebie w odwrotnym kierunu niż w innym segmencie/segmentach.

| |

| − | | |

| − | w 1914 roku Brown utworzył podrodzinę Saurolophinae, zawierającą hadrozaurydy noszące szczątkowy grzebień

| |

| − | Brett-Surman zauważył, że wszystkie hadrozaurydy mogą byc przyporządkowane do jednej z dwóch podrodzin - Hadrosaurinae lub Lambeosaurinae, gdzie Saurolophinae zawierajacym się w Hadrozaurynach.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Duży okaz z Mongolii został wydobyty z formacji nemegt podczas Polsko-Mongolskich ekspedycji paleontologicznych. Przez Ryszarda Gradińskiego, Józefa Kazmierczaka i Jerzego Lefelda. Mierzył 12 metrów długości. S. angus to najbardziej obfity azjatycki hadrozaur, znany zarówno z Ałtan Uła jak i Tsagan hushu, i wydaje się być dominującym roślinożercą w formacji Nemegt

| |

| − | | |

| − | Bazując na badaniach czaszi młodego osobnik s.angu m&o 1979 stwierdziły, że jak u innych ptasiomiednicsznych - dwie kości ponadoczodołwe są inkorporowane w górną granicę oczodołu czaszki. M&o 1979 zasugerowały rówmnjież, że utrata ponadoczodołowych jest obecna zarówno u prymitywncyh lambeozaurynow jak i hadrozaurynów, podczas gdy u bardziej zaawansowanych lambezoaurynów ponadoczodołwe mogły być początkowo częścią obręczy oczodołowej, ulegając fuzji z przedczołową i zaoczodołową w czasie ontogenezy.

| |

| − | Wykazały również 1981, że wysotek k. nosowej jest prawdopodobnie wydrążony, a lity jedynie w szczytowym końcu. Zasugerowały, że grzebien służył do zwiększenia powierzchni oddechowej otworu nosowego, mając tym samym funkcję regulacji termicznej. Również do pewnego stopnia utrata u hadrozaurynów stawów pomiędzy częściami czaszki, zwłaszcza pomiędzy dolną gałęzią . przedszczękwoej i szczekową, służyła jako coś w rodzaju amortyzator wstrząsów, chroniacy delikatną struktruę nozdrzy przed uszkodzeniem w trakcie żucia.

| |

| − | | |

| − | S. kryschtofovici - n.d. - opiera się na bliższym końcu lewej k. kulszowej, znalezionej w Beiliyie Kruchi, w północnym Heilungchiang w Chinach. Została opisana przez Riabinina w 1930b. Jest obecnie uznawany za synonim s. ang.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Glut 2001

| |

| − | w 1999 Ishigaki doniósł o odryciu ponad 600 dużych (25-155 cm długości), trójpalczastych tropów z późnej kredy w Bugeen Tsav i Gurilin Tsav w zachodniej części postyni Gobi.

| |

| − | Zostały odryte w latach 1995-1998 przez Hayshsibara Museum of Natural Science-Mongolian Paleontological Center Joint Paleoncological Expedicion Team, zostały przypisane do zaurolofa, bazując na obfitości kościu należących do tego rodzaju na tym samym terenie w tym samym czasie.

| |

| − | Jak twierdzi Ishigakio, ponad 15 000 tropów dinozaurów z 11 różnych lokacji na Gobi zopstały znalezionych podczas tej ekspedycji - również ankylozaurydów i teropodów.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Ishigaki,S.

| |

| − | Abundant Dinosaur Footprints from Upper Cretaceous of Gobi

| |

| − | Desert, Mongolia

| |

| − | Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Vol. 19, Supplement to Number

| |

| − | 3, p. 54A, 1999

| |

| − | | |

| − | Glut 1997

| |

| − | | |

| − | Etymologia: z greckiego - "sauros" = "jaszczur" + "lophus" - grzebień. Grzebieniasty jaszczur

| |

| − | Znane z lokacji: formacja Horseshoe Canyon (Alberta, Kanada)

| |

| − | formacja Nemegt (Omnogov; Mongolia)

| |

| − | neinazwana formacja w Heilungchang, Chiny

| |

| − | | |

| − | znany materiał: 18 okazów (1997), kompletny szkielet, dwie kompletne izolowane czaszki, zarówno

| |

| − | | |

| − | dojrzałych jak i młodocianych (juwenilnych) osobników.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Holotyp: AMNH 5220, niemal kompletny szkielet z odcisiem skóry

| |

| − | Paratyp: AMNH 5221 - nieartykułowana czaszka

| |

| − | Plezjotyp: AMNH 5225 - kompletna k. kulszowa

| |

| − | | |

| − | Diagnoza:

| |

| − | S. osborni (Brown 1912b)

| |

| − | czaszka z długim, tylnim kostnym grzebieniem tworzonym przez wydlużenie kosci czołowej i

| |

| − | | |

| − | nosowej;

| |

| − | k. lzowa bardzo długa, wyższy wyroste k. przedszczękowej wznosi się do tylnej granicy nozdrzy

| |

| − | promieniowa i barkowa podobnej długości

| |

| − | 8 kręgów krzyżowych

| |

| − | kulszowa kończy się wznosząca "stopa"

| |

| − | łonowa z któtkim wznoszącym się przednio ostrzem

| |

| − | biodrowa silnie łukowata, przedni wyrostek zakrzywiony w dół, cienki płat

| |

| − | czwarty krętarz k. udowej poniżej połowy trzony

| |

| − | palce II i IV krótie

| |

| − | | |

| − | S. angustirostris

| |

| − | -węzsza czaszka i dłuższy grzebień (Rozhdestevensky 1957)

| |

| − | Maryańska & Osmólska 1981a:

| |

| − | -krósze nozdrza

| |

| − | -krótsza i głębsza k. łzowa

| |

| − | -przednia część żuchwy wydłużona w długi wyrostek, wchodzący klinem między k. szczękową i łzową

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Saurolophus to pierwszy kanadjski dinozaur znany z niemal kompletnego szkieletu.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Historia odkrycia:

| |

| − | 1911 - Amerykańskie Muzeum historii naturalnej z Horseshoe Canyon Formation, wówczas znane jako

| |

| − | | |

| − | formacja Edmonton.

| |

| − | 1912 - Barnum Brown opisuje holotyp i czasszkę; szkielet zostaje wypreparowany i wystawiony w

| |

| − | | |

| − | amerykańskim muzeum historii naturalnej

| |

| − | 1913 - Barnum Brown opisuje Saurolophus osborni.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Saurolophus to duzy hadrozaur = holotypowysz szkielet mierzył ok. 8,4 m; 2 tony (Paul, 1988 -

| |

| − | | |

| − | Glut, 1997)

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Najbardziej wyróżniającą się cechą zaurolofa był kostny grzebień, który wznosi się ponad kąt

| |

| − | | |

| − | czaszki niczym kolec. Brown 1912b,1913a porównywał grzebień do tego, ubecnego u kameleona,

| |

| − | | |

| − | sugerując, że służył on do jako miejsce przyczepu silnych mięśni.

| |

| − | Dodson 1975 - sugeruje, że grzebienie mogły mieć znaczenie w identyfikacji płciowej.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Pierścień sklerotyczny z holotypowej czaszki wykazuje, że oko było znacznie mniejsze niż

| |

| − | | |

| − | oczodół. Ruszeel 1940a wykazal, że płyty pierścienia sklerotycznego nie są szeregowe w jednym

| |

| − | | |

| − | kierunku, ale raczej mają jeden lub więcej segmentów w których płytki nachodzą na siebie w

| |

| − | | |

| − | odwrotnym kierunu niż w innym segmencie/segmentach.

| |

| − | | |

| − | w 1914 roku Brown utworzył podrodzinę Saurolophinae, zawierającą hadrozaurydy noszące szczątkowy

| |

| − | | |

| − | grzebień

| |

| − | Brett-Surman zauważył, że wszystkie hadrozaurydy mogą byc przyporządkowane do jednej z dwóch

| |

| − | | |

| − | podrodzin - Hadrosaurinae lub Lambeosaurinae, gdzie Saurolophinae zawierajacym się w

| |

| − | | |

| − | Hadrozaurynach.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Duży okaz z Mongolii został wydobyty z formacji nemegt podczas Polsko-Mongolskich ekspedycji

| |

| − | | |

| − | paleontologicznych. Przez Ryszarda Gradińskiego, Józefa Kazmierczaka i Jerzego Lefelda. Mierzył

| |

| − | | |

| − | 12 metrów długości. S. angus to najbardziej obfity azjatycki hadrozaur, znany zarówno z Ałtan

| |

| − | | |

| − | Uła jak i Tsagan hushu, i wydaje się być dominującym roślinożercą w formacji Nemegt

| |

| − | | |

| − | Bazując na badaniach czaszi młodego osobnik s.angu m&o 1979 stwierdziły, że jak u innych

| |

| − | | |

| − | ptasiomiednicsznych - dwie kości ponadoczodołwe są inkorporowane w górną granicę oczodołu

| |

| − | | |

| − | czaszki. M&o 1979 zasugerowały rówmnjież, że utrata ponadoczodołowych jest obecna zarówno u

| |

| − | | |

| − | prymitywncyh lambeozaurynow jak i hadrozaurynów, podczas gdy u bardziej zaawansowanych

| |

| − | | |

| − | lambezoaurynów ponadoczodołwe mogły być początkowo częścią obręczy oczodołowej, ulegając fuzji z

| |

| − | | |

| − | przedczołową i zaoczodołową w czasie ontogenezy.

| |

| − | Wykazały również 1981, że wysotek k. nosowej jest prawdopodobnie wydrążony, a lity jedynie w

| |

| − | | |

| − | szczytowym końcu. Zasugerowały, że grzebien służył do zwiększenia powierzchni oddechowej otworu

| |

| − | | |

| − | nosowego, mając tym samym funkcję regulacji termicznej. Również do pewnego stopnia utrata u

| |

| − | | |

| − | hadrozaurynów stawów pomiędzy częściami czaszki, zwłaszcza pomiędzy dolną gałęzią .

| |

| − | | |

| − | przedszczękwoej i szczekową, służyła jako coś w rodzaju amortyzator wstrząsów, chroniacy

| |

| − | | |

| − | delikatną struktruę nozdrzy przed uszkodzeniem w trakcie żucia.

| |

| − | | |

| − | S. kryschtofovici - n.d. - opiera się na bliższym końcu lewej k. kulszowej, znalezionej w

| |

| − | | |

| − | Beiliyie Kruchi, w północnym Heilungchiang w Chinach. Została opisana przez Riabinina w 1930b.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Jest obecnie uznawany za synonim s. ang.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Glut 2001

| |

| − | w 1999 Ishigaki doniósł o odryciu ponad 600 dużych (25-155 cm długości), trójpalczastych tropów

| |

| − | | |

| − | z późnej kredy w Bugeen Tsav i Gurilin Tsav w zachodniej części postyni Gobi.

| |

| − | Zostały odryte w latach 1995-1998 przez Hayshsibara Museum of Natural Science-Mongolian

| |

| − | | |

| − | Paleontological Center Joint Paleoncological Expedicion Team, zostały przypisane do zaurolofa,

| |

| − | | |

| − | bazując na obfitości kościu należących do tego rodzaju na tym samym terenie w tym samym czasie.

| |

| − | Jak twierdzi Ishigakio, ponad 15 000 tropów dinozaurów z 11 różnych lokacji na Gobi zopstały

| |

| − | | |

| − | znalezionych podczas tej ekspedycji - również ankylozaurydów i teropodów.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Ishigaki,S.

| |

| − | Abundant Dinosaur Footprints from Upper Cretaceous of Gobi

| |

| − | Desert, Mongolia

| |

| − | Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Vol. 19, Supplement to Number

| |

| − | 3, p. 54A, 1999

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ______________

| |

| − | Barnum brown, 2010

| |

| − | | |

| − | p.141

| |

| − | While the rest of the crew quarried — including George Sternberg, who

| |

| − | arrived on July 7 — Brown focused on prospecting. In all, he lists thirtysix

| |

| − | major specimens, including fifteen hadrosaurs (such as Saurolophus),

| |

| − | nine ceratopsians, three ankylosaurs, four ornithomimids (presumably

| |

| − | Struthiomimus), and one plesiosaur.42 Although plesiosaur specimens are

| |

| − | uncommon in these nonmarine sediments, they are not really unusual.

| |

| − | Paleontologists now suspect that they swam up active river channels either

| |

| − | in search of ballast stones or to shed parasites. In this early phase of the

| |

| − | expedition, Brown downplayed the competition with Ottawa, reporting

| |

| − | to Matthew: “The Ottawa party are somewhere . . . [on the river] in the

| |

| − | Edmonton formation approximately at Drumheller twenty miles below

| |

| − | which does not disturb me as that is in the lower part of the beds [which

| |

| − | produce] chiefly quarry [i.e., bonebed] specimens. As long as they are there I

| |

| − | shall concentrate the whole party in this formation where the exposures are

| |

| − | best.” 43

| |

| − | | |

| − | p. 151

| |

| − | Brown’s discoveries continue to resonate. Today, paleontologists still recognize

| |

| − | eight species of nonavian dinosaurs based on holotypes that Brown

| |

| − | and his crews collected from the Dinosaur Park Formation, which he

| |

| − | called the Belly River Beds: three horned dinosaurs, Chasmosaurus kaiseni

| |

| − | (AMNH 5401), Monoclonius cutleri (AMNH 5427), and Styracosaurus

| |

| − | parksi (AMNH 5372); two duckbills, Corythosaurus casuarius (AMNH

| |

| − | 5240) and Prosaurolophus maximus (AMNH 5386); a small carnivorous

| |

| − | theropod, Dromaeosaurus albertensis (AMNH 5356); and a dome-headed

| |

| − | pacycephalosaur, Ornatotholus browni (AMNH 5450), which probably

| |

| − | represents a juvenile Stegoceras.94 The collections of Brown’s crews from

| |

| − | the Edmonton Group allowed Brown to describe four other new species as

| |

| − | well: the horned dinosaurs Anchiceratops ornatus and Leptoceratops gracilis

| |

| − | and two duckbilled dinosaurs, Hypacrosaurus altispinus and Saurolophus

| |

| − | osborni. Today, Brown’s old quarries are being located, based on photos

| |

| − | he took and using as evidence objects that he and his crews left behind,

| |

| − | such as plaster, scrap lumber, and newspaper used to make the specimen

| |

| − | casts.95 This project is being conducted in conjunction with GPS survey

| |

| − | work in Dinosaur Provincial Park, to preserve not only the locality data

| |

| − | for the specimens but also their stratigraphic context, which allows for a

| |

| − | more comprehensive understanding of when the animals lived and how

| |

| − | the fauna evolved some 75 million years ago.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | __________

| |

| − | Chinese Fossil Vertebrates

| |

| − | | |

| − | Nemegtian Vertebrates

| |

| − | The vertebrate fossil assemblage of the Nemegt Formation in Mongolia is the

| |

| − | basis of the Nemegtian land-vertebrate faunachron (Jerzykiewicz and Russell

| |

| − | 1991: 370). Characteristic taxa are the theropod Tarbosaurus, the sauropods

| |

| − | Nemegtosaurus (see figure 9-17) and Opisthocoelicaudia and the hadrosaurid

| |

| − | Saurolophus. In northeastern China, Riabinin (1930) described Tarbosaurus?,

| |

| − | Tanius, and Saurolophus from strata in Heilongjiang of Nemegtian age. In Xinjiang,

| |

| − | the Subashi Formation yields Tarbosarus and Nemegtosaurus and thus is

| |

| − | of Nemegtian age (Dong 1977, 1997f and h).

| |

| − | I consider the vertebrate fauna of the upper Wangshi Formation of Shandong

| |

| − | (see figure 9-6) (Z. Cheng et al. 1995; X. Wang 1996) to be of Nemegtian age,

| |

| − | although this correlation is not certain. It has yielded the tyrannosaurid Chingkankousaurus

| |

| − | fragilis Young, the hadrosaurids Tanius sinensis Wiman (= T. chingkankouensis

| |

| − | Young, = T. laiyangensis Zhen), Shantungosaurus giganteus Hu, and

| |

| − | Tsintaosaurus spinorhinus Young (see figure 9-18); the ankylosaur Pinacosaurus

| |

| − | cf. P. grangeri Gilmore (see Buffetaut 1995); the pachycephalosaurid Micropachycephalosaurus

| |

| − | hongtuyanensis Dong; and dinosaur eggs (Wiman 1929;

| |

| − | Chow 1951; Young 1958b; Dong 1978, 1992). However, note that Pinacosaurus

| |

| − | suggests that part of the Wangshi Series may be of Djadokhtan age (Buffetaut

| |

| − | 1995; Buffetaut and Tong 1995), as does the suggestion that Bactrosaurus

| |

| − | johnsoni from Iren Dabasu is a synonym of Tanius sinensis (Z. Cheng et al.

| |

| − | 1995).

| |

| − | What may be even younger dinosaur dominated assemblages from China

| |

| − | must be assigned a Nemegtian age because they cannot at present be distin-

| |

| − | guished from the classic Nemegtian assemblage. Nemegtian thus represents the

| |

| − | last interval of Cretaceous time that can be recognized from fossil vertebrates in

| |

| − | China. The Nemegtian hadrosaurid Saurolophus Brown is an early Maastrichtian

| |

| − | genus in North America (Horshoe Canyon Formation, Alberta). This suggests

| |

| − | an early Maastrichtian age for at least part of the Nemegtian.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ______

| |

| − | Flaming Cliffs

| |

| − | | |

| − | 131-132

| |

| − | At Altan Ula, Efremov's party found skeletons of seven giant

| |

| − | hadrosaurs embedded in close association in a very hard red sandstone,

| |

| − | seemingly the product of a mass death and burial. T h e site was called the

| |

| − | "Dragons' Tomb." T h e skeletons turned out to be rather undragonly herbivores,

| |

| − | the duckbill Saurolophus angustirostris, named for the solid crest on

| |

| − | the back of the top of the head. Saurolophus was a big hadrosaur, with

| |

| − | adults reaching lengths of forty feet and some individuals looming over

| |

| − | twenty-five feet high.

| |

| − | Hadrosaurs of the Cretaceous Gobi, as well as those in North America,

| |

| − | were built to get around quite adeptly on land, but they also may have

| |

| − | entered the water to feed on plants. T h e abundance of lacustrine and fluvial

| |

| − | beds near the "Dragons' Tomb" probably provided a rich Saurolophus

| |

| − | habitat. It is noteworthy that this locality contained not only skeletons but

| |

| − | also remarkable fossil evidence for soft parts. Bubbly or pebbly impressions

| |

| − | of skin were found in association with the skeletons. T h e fossilized "chunks

| |

| − | of skin" are actually casts made from reverse-image molds pressed into the

| |

| − | substrate by these ponderous hulks as they lay in the mud to rest, feed, or

| |

| − | die. Skin impressions of hadrosaurs are known from other places, and in

| |

| − | some cases they are truly spectacular. T h e world's premier specimen resides

| |

| − | in the recently renovated dinosaur halls at the American Museum of Natural

| |

| − | History, essentially a cast of the skin of the entire body—a complete

| |

| − | mud "mummy"—of a North American Edmontosaurus, a distant relative of

| |

| − | Saurolophus.

| |

| − | All hadrosaurs have a distinctive battery of closely packed teeth,

| |

| − | whose crown surfaces combine to form a mill. Ridges acted together like a

| |

| − | rasping file that efficiently broke down tough vegetation. There are actually

| |

| − | hundreds of teeth in a hadrosaur jaw but they work together as two sets

| |

| − | of grinding mills, one set in each side of the upper and lower jaws. The

| |

| − | skull roof and the back of the jaw show prominent struts and ledges of

| |

| − | bone. These served as attachments for muscles whose contraction moved

| |

| − | the jaws back and forth for effective milling. The skeleton itself is appointed

| |

| − | with a rather short but very flexible and sinuous neck, small fore

| |

| − | limbs, but large elongated hind limbs. The vertebrae of the massive and

| |

| − | lengthy tail are equipped with extended splints or chevron bones, which

| |

| − | project downward from the body of each tail (or caudal) vertebra. Covered

| |

| − | with flesh, these would give the hadrosaur tail its notable flattened appearance.

| |

| − | One of the most remarkable features of the vertebral column in

| |

| − | hadrosaurs, as well as in certain other dinosaurs, is the intricate weaving of

| |

| − | ossified tendons. These crisscross among the spines, extending above each

| |

| − | vertebra in the back (lumbar) and the tail region. They seem to be there for

| |

| − | support of the back; to prevent the trusswork of the vertebral column from

| |

| − | sagging against that great mass of muscle, fat, and internal organs.

| |

| − | Something, of course, had to feed on big herbivores like hadrosaurs,

| |

| − | and the best candidate in the Gobi is the tyrannosaurid Tarbosaurus. During

| |

| − | the expeditions of the 1940s the Russian team found three skeletons of

| |

| − | Tarbosaurus in the Nemegt Formation at the Dragons' Tomb site, where

| |

| − | several Saurolophus lay. Tarbosaurus (the name means alarming reptile) is

| |

| − | very like the more familiar Tyrannosaurus and doubtless a close relative.

| |

| − | Tarbosaurus is big. Some skeletons are up to forty-six feet long, longer than

| |

| − | Tyrannosaurus by more than six feet (although apparently it stood a bit

| |

| − | shorter than the tyrant king). Like sauropods, these animals required enormous

| |

| − | amounts of food, in this case, meat. They were well built for the purpose.

| |

| − | T h e skull of Tarbosaurus is more than four feet long. Its jaws are studded

| |

| − | with recurved razor-edged teeth, some nearly six inches long. The

| |

| − | three toes of the hind feet are appointed with viciously sharpened and

| |

| − | curved claws. The lengthy hindlimb bones show scars for attachment of

| |

| − | enormous muscles. Everything about it suggests power and agility, an animal

| |

| − | capable of lunging its massive body at a hapless hadrosaur and disemboweling

| |

| − | it in an instant.

| |

| − | | |

| − | 167-169

| |

| − | D R I F T I N G D I N O S A U R S

| |

| − | This enrichment in the texture of landforms, oceans and seas, and certainly

| |

| − | the isolation of many regions, fueled the momentum for evolution and divergence.

| |

| − | Geographic isolation—by seas, rivers, mountain ranges, or contrasting

| |

| − | climate—is a major driving force of speciation because populations

| |

| − | that at one time exchanged genes are suddenly cut off from one another.

| |

| − | They then evolve along their own pathways. Likewise, this differentiation

| |

| − | can be expressed by the divergence among groups containing those species.

| |

| − | So Cretaceous dinosaurs can be divided into various regional fiefdoms. To

| |

| − | appreciate this, we must abandon a mind set that makes us view continents

| |

| − | as they are today. Remember that in the Northern Hemisphere, eastern

| |

| − | Asia and western North America were broadly connected in the region of

| |

| − | the Bering Sea. On the other hand, eastern North America was cut off

| |

| − | from this complex by a great seaway. It was, however, connected, at times,

| |

| − | to broken-up parts of Europe in the North Atlantic region. Thus we can

| |

| − | think of two continents—let's call them Asiamerica and Euroatlantis—instead

| |

| − | of a single northern continent or the customary division of North

| |

| − | America and Eurasia. Expectedly, dinosaur divergence mirrors this conti

| |

| − | nental pattern. The armored ankylosaurids, the horned ceratopsians, and

| |

| − | the more specialized hadrosaurs, like Saurolophus and the crested Corythosaurus,

| |

| − | were evolving in the Gobi and the Rocky Mountain region and

| |

| − | presumably parts in between. In contrast, primarily more generalized

| |

| − | hadrosaurs claimed Europe and eastern North America. Although the

| |

| − | dromaeosaurids (the group that includes Velociraptor) ranged broadly over

| |

| − | the northern landmasses, they were virtually excluded from the southern

| |

| − | continents. South of the equator there were a number of groups common

| |

| − | to the northern continents—iguanodontids, hypsilophodontids, and

| |

| − | sauropods—but these were distinctively different genera or even higher

| |

| − | groups containing several genera. Also, our denizens of the Gobi, the protoceratopsids,

| |

| − | as well as their ceratopsid relatives were notably absent from

| |

| − | the southern continents.

| |

| − | We see here, then, a picture of dinosaurs and continents that jives

| |

| − | poorly with Osborn's and Andrews' concept of a center of origin for vertebrate

| |

| − | evolution in Asia. What the pattern does suggest is a history of dinosaur

| |

| − | differentiation that closely tracked the breakup of the continents.

| |

| − | Originally, certain groups of dinosaurs ranged broadly over the sutured

| |

| − | landmasses. Their descendants were allowed the opportunity of divergence

| |

| − | once these landmasses were separated. Central Asia was certainly an im-

| |

| − | portant region for the emergence of certain dinosaur groups, but it wasn't

| |

| − | the only such region.

| |

| − | | |

| − | T H E C O M F O R T A B L E C O R R I D O R

| |

| − | Another point that has much interested paleontologists concerns the affinity

| |

| − | of Cretaceous dinosaurs between two major regions of the world—

| |

| − | Central Asia and western North America. At closer inspection, the resemblances

| |

| − | between these two faunas are even more striking. Velociraptor is

| |

| − | very much like another somewhat larger dromaeosaur from North America,

| |

| − | Deinonychus. The hadrosaur Saurolophus is known from both regions.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | 194

| |

| − | On July 27, the day after the departure of the BBC, a small team—

| |

| − | Mark, Jim, Lowell, Dashzeveg, and I—struck out with two Mitsus and

| |

| − | Mangal Jal's G A Z to a wholly new area. This sortie represented our farthest

| |

| − | push westward—to a frontier as hot and windy and uninhabited as

| |

| − | lonely Kheerman Tsav, a maze of sandstone cliffs and spires known as Bugin

| |

| − | Tsav. T h e Russians and Mongolians had worked this place extensively,

| |

| − | but we had never been there and we were anxious to see it. Bugin Tsav,

| |

| − | whose baroquely intricate canyons exposed the multihued Nemegt Formation,

| |

| − | had been declared a national park. The park lay about twenty miles

| |

| − | west and slightly north of Naran Bulak, the lonely windswept complement

| |

| − | to Kheerman Tsav directly to its south. Despite the seclusion of Bugin

| |

| − | Tsav, we had no intention of removing dinosaur skeletons. We were simply

| |

| − | interested in reconnoitering the place for skeletons that might warrant

| |

| − | work there—pending permission for major excavation—the next field season.

| |

| − | We did indeed find the myriad canyons, washes, cliffs, and hills of

| |

| − | Bugin Tsav full of big bones. Some of these were the skeletons of lumbering

| |

| − | sauropods or hadrosaurs. At one spot, I spied a long string of tail vertebrae

| |

| − | snaking its way around the edge of a hill. As I walked around the

| |

| − | other side of this knob, I was amazed to see more of the skeleton, part of

| |

| − | the ribs and the neck vertebrae exposed. T h e beasts of Bugin Tsav were of

| |

| − | mountain-sized proportions. They can be discovered from a distance. One

| |

| − | especially hot July in the subsequent field season of 1993 we were driving

| |

| − | through these extensive badlands when Mark suddenly told me to stop the

| |

| − | car. Fifty yards back, the giant skeleton of a Saurolophus, a forty-foot-long

| |

| − | duck-billed dinosaur, was exposed on top of a small sand hill. A Tarbosaurus

| |

| − | foot, with its distinctive tripod of digits and its long claws, rested

| |

| − | on top of the duck-billed skeleton, as if the carnosaur were staking a claim

| |

| − | to the carcass.

| |

| − | | |

| − | 215

| |

| − | This pattern of head accouterments and their possible bearing on social

| |

| − | rank or role is not confined to ceratopsians. The duck-billed

| |

| − | hadrosaurs are differentiated mainly by the development (or lack thereof)

| |

| − | of their emblematic head crests. Some forms have virtually no crest at all.

| |

| − | This may have been a primitive feature of the group, which is found in

| |

| − | both early and later hadrosaurs (remember, the fossil record doesn't always

| |

| − | perfectly mirror the advancement of steps in evolution). In crested forms

| |

| − | the name of the game is weird elaboration and variation. Saurolophus, our

| |

| − | beast from the Gobi (also known from North America), has a prominent

| |

| − | bony ridge on top of the snout and face that ends behind in a small spike.

| |

| − | The Gobi species of this group shows some distinctiveness in its somewhat

| |

| − | longer and more fan-shaped head spike. But the really bizarre species are

| |

| − | some of the North American forms. An extremely broad platelike crest is

| |

| − | known in Corythosaurus, and there is a long bony tube that extends backward

| |

| − | nearly three and a half feet from the skull of Parasaurolophus. Stranger

| |

| − | still is the fact that the nasal passages actually extend for some distance into

| |

| − | these hollow crests. Their caliber and design vary, just like the differences

| |

| − | one sees in the passageways of trombones, saxophones, and tubas. Not all

| |

| − | these crests are hollow; for example, hadrosaurines, which include the

| |

| − | Gobi beast Saurolophus, lacked such passageways.

| |

| − | These crests have excited some paleontologists to a considerable degree

| |

| − | and there is no shortage of speculation on their function. As with

| |

| − | many reconstructions of fossils, none of these explanations can be decisively

| |

| − | verified, nor are any of them necessarily false. To complicate matters,

| |

| − | the crests may have taken on different functions in different species. Yet it

| |

| − | is possible to determine which of these ideas make more sense. The suggested

| |

| − | use of the crests for breathing, air storage, or air trapping while underwater

| |

| − | seems on the whole rather unlikely. These beasts were adept in

| |

| − | water, and they might have retreated to lakes, rivers, and seas to escape a

| |

| − | rapacious Tarbosaurus or Tyrannosaurus. Nonetheless, their well-supported

| |

| − | bodies and their tooth batteries indicate that hadrosaurs probably spent

| |

| − | most of their time on land, eating relatively tough branches and leaves of

| |

| − | trees and bushes. Fossilized conifer needles, branches, deciduous foliage,

| |

| − | and numerous small seeds and fruits have been claimed to be the "stomach

| |

| − | contents" of a hadrosaur Edmontosaurus. If this identity is correct, one can

| |

| − | assume that the duckbills did not have an overpowering need to feed underwater

| |

| − | for long periods of time.

| |

| − | For lack of a better notion, the correlation between the hadrosaur

| |

| − | crest development and a signaling function endures. T h e idea was refined

| |

| − | starting with some thoughts expressed by the paleontologist James Hopson

| |

| − | at the University of Chicago and later elaborated by Peter Dodson at

| |

| − | the University of Pennsylvania and Dave Weishampel at Johns Hopkins

| |

| − | University. Animals that use such obvious cues today often share a number

| |

| − | of qualities. They have a keen sense of eyesight and/or hearing. They are

| |

| − | often social and sexually dimorphic (males are larger and more aggressively

| |

| − | built and armed than females, or vice versa), with individuals in frequent

| |

| − | threatening behavior or combat for competition for mates of the opposite

| |

| − | sex. Finally, species living in the same area that rely on such signals, like the

| |

| − | antelopes of the Serengeti, often have very distinctive, highly different

| |

| − | head ornaments like horns, to cue their own species.

| |

| − | Hadrosaurs in a broad sense fit this picture. They have large eye sock

| |

| − | ets and intricate ear bones, indicating acute vision and hearing. Weishampel

| |

| − | developed some ingenious experiments to suggest that the hollow

| |

| − | tubular crests of Parasaurolophus and other hadrosaurs were effective sound

| |

| − | resonators. Moreover, Dodson's studies have shown that crests are accentuated

| |

| − | in adults and, even in the case of adults, both big-crested and

| |

| − | smaller-crested individuals are found in samples representing the same

| |

| − | species. As in the case of the ceratopsians, this suggests a difference in the

| |

| − | sexes pertaining to social behavior. Either the males or the females were establishing

| |

| − | mating hierarchies or involved in rituals of signaling threats and

| |

| − | combat. Finally, in a few localities in North America more than six different

| |

| − | species are found together and most of these are easily discriminated

| |

| − | by their varying head crests.

| |

| − | What about our Gobi creature Saurolophus} One might conjure up a

| |

| − | picture of massive animals feeding in the marshes and deeps of a lake.

| |

| − | Crests on some individuals may have indicated their position in the mating

| |

| − | hierarchy, a signal backed up by the honking sounds of protective

| |

| − | males. Is this vision the reality of seventy-five million years before Efremov

| |

| − | and his band came upon hadrosaur skeletons in the Nemegt Valley? We'll

| |

| − | never know. Some ideas, like the use of crests for visual cues, seem to match

| |

| − | some circumstantial evidence. Elaboration of the scene is not so easy however.

| |

| − | The myriad published color schemes for dinosaur crests, shields,

| |

| − | trunks, and tails are purely imaginary. At any rate it's fun to think about

| |

| − | them.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ____________

| |

| − | Dragon Hunter

| |

| − | 374

| |

| − | After their five years of work in both hemispheres, the Canadians

| |

| − | and Chinese were able to demonstrate that large sections of the continental

| |

| − | masses were not covered by oceans during the late Cretaceous

| |

| − | and were connected in their northernmost latitudes by land bridges. As

| |

| − | Michael J. Novacek has pointed out, a fairly wide variety of dinosaurs

| |

| − | made use of these intercontinental links to travel between Asia and

| |

| − | North America. For example, the hadrosaur Saurolophus is found in

| |

| − | both regions; Velociraptor, ankylosaurs, and Oviraptor had close relatives

| |

| − | in North America, as did larbosaurus, a slightly smaller version of

| |

| − | Tyrannosaurus, which are so much alike that some paleontologists believe

| |

| − | they should both be classified as a single species. And a theropod

| |

| − | found in the Gobi, Sauromithoides, has a counterpart known as

| |

| − | Troodon that inhabited Alberta, Wyoming, and Montana.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ____________________---

| |

| − | Currie

| |

| − | | |

| − | American Dinosaurs

| |

| − | A close relationship, possibly at the species

| |

| − | level, of Tyrannosaurus with the Asiatic Tarbosaurus

| |

| − | is recognized. Other evidence for exchange is better

| |

| − | documented by Canadian dinosaurs, notably the ha-

| |

| − | drosaurine Saurolophus. Due to the relatively impoverished

| |

| − | faunas of the Judith River Formation and

| |

| − | dearth of early Maastrichtian dinosaurs in the United

| |

| − | States, coupled with the relatively restricted area of

| |

| − | late Maastrichtian strata in Alberta and Saskatchewan,

| |

| − | faunal overlap between the United States and

| |

| − | Canada is not as great as expected, and the greater

| |

| − | diversity and completeness of specimens favors Canada.

| |

| − | | |

| − | American Museum of Natural History

| |

| − | In 1902 Barnum Brown led an AMNH expedition

| |

| − | to the Cretaceous beds of the HELL CREEK region

| |

| − | of Montana. This resulted in the first known specimen

| |

| − | of Tyrannosaurus rex, in 1902, and a second,

| |

| − | more highly preserved specimen in approximately

| |

| − | 1908. This second specimen is generally regarded

| |

| − | as the most famous dinosaur fossil in the world

| |

| − | and has long been a centerpiece of the AMNH.

| |

| − | Brown went on to lead museum-sponsored expeditions

| |

| − | in 1910–1915 to the Red Deer River region of

| |

| − | Alberta, Canada. These also yielded rich discoveries,

| |

| − | especially of hadrosaurs such as Saurolophus and

| |

| − | Corythosaurus. In the 1930s another AMNH expedition

| |

| − | led by Brown excavated a large collection of

| |

| − | Jurassic fossils from the Howe Ranch site in

| |

| − | Wyoming.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Canadian Dinosaurs

| |

| − | The late Campanian–early Maastrichtian beds of

| |

| − | the Horseshoe Canyon Formation near Drumheller

| |

| − | are also rich with skeletons of indeterminate theropods

| |

| − | (Richardoestesia), dromaeosaurids (Dromaeosaurus

| |

| − | and Saurornitholestes), caenagnathids (Chirostenotes),

| |

| − | tyrannosaurids (Aublysodon, Albertosaurus,

| |

| − | and Daspletosaurus), ornithomimids (Struthiomimus,

| |

| − | Dromicieomimus, and Ornithomimus), troodontids

| |

| − | (Troodon), hypsilophodontids (Parksosaurus), hadrosaurs

| |

| − | (Edmontosaurus, Saurolophus, and Hypacrosaurus),

| |

| − | pachycephalosaurids (Stegoceras), ceratopsids

| |

| − | (Anchiceratops, Arrhinoceratops, and Pachyrhinosaurus),

| |

| − | and ankylosaurs (Edmontonia and Euoplocephalus)

| |

| − | | |

| − | Edmonton Group 230

| |

| − | The Edmonton Group is an important dinosaurand

| |

| − | coal-bearing unit in the south-central portion

| |

| − | of the Alberta Basin that ranges in age from latest

| |

| − | Campanian to early Danian (Early Paleocene) and

| |

| − | thus spans the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary. It

| |

| − | comprises a southeastward-thinning, largely nonmarine

| |

| − | to shallow marine clastic wedge that is exposed

| |

| − | in modern drainages throughout south-central Alberta.

| |

| − | It conformably overlies and interfingers with

| |

| − | marine shales of the late Campanian Bearpaw Formation

| |

| − | and is overlain unconformably by sandstones of

| |

| − | the Late Paleocene Paskapoo Formation. It has been

| |

| − | a source of important dinosaur and other fossil vertebrate,

| |

| − | invertebrate, and plant discoveries since the

| |

| − | early part of the 20th century and, recently, has figured

| |

| − | importantly in studies of terminal Cretaceous

| |

| − | extinctions.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Mesozoic 450

| |

| − | The Laurasian continents appeared to

| |

| − | continue biotic exchange through the Mesozoic, but

| |

| − | the faunas are not cosmopolitan; seemingly they were

| |

| − | interrupted either by marine excursions (eastern and

| |

| − | western North America; North America–Europe) or

| |

| − | by ecological barriers (North America–Asia) at least

| |

| − | from time to time. For example, congeneric hadrosaurs

| |

| − | (Saurolophus) are known in both North America

| |

| − | and Asia in the Maastrichtian; different genera of

| |

| − | closely related pachycephlosaurs are known from the

| |

| − | Campanian and Maastrichtian of both continents;

| |

| − | basal ceratopsians (Psittacosaurus) are known from

| |

| − | Asia but not North America, protoceratopsids are

| |

| − | known from both continents, but Ceratopsidae are

| |

| − | restricted to the Western Hemisphere.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Mongolian Dinosaurs 480

| |

| − | Only two hadrosaurs have been described so far.

| |

| − | Saurolophus angustirostris was a huge animal, up to 14

| |

| − | m long. Like the North American species, the nasals

| |

| − | extend posterodorsally above the orbit to form a solid

| |

| − | crest, which is supported from behind by upraised

| |

| − | frontal buttresses. This is one of the most common

| |

| − | Mongolian dinosaurs from the latest Cretaceous beds,

| |

| − | and there are many fine specimens that even include

| |

| − | abundant skin impressions. Barsboldia sicinskii is a

| |

| − | lambeosaurine with very long and club-shaped neural

| |

| − | spines in the dorsal vertebrae.

| |

| − | | |

| − | formacja Nemegt 472

| |

| − | The assemblage of dinosaurs found in the Nemegt

| |

| − | Formation contains theropods, sauropods, hadrosaurids,

| |

| − | pachycephalosaurs, and ankylosaurs. A distinctive

| |

| − | character of this fauna is the unusually high

| |

| − | diversity of theropods, which includes 14 monospecific

| |

| − | genera belonging to at least six families. Among

| |

| − | these theropods, Tarbosaurus bataar and Gallimimus

| |

| − | bullatus are represented by 10 or more specimens,

| |

| − | whereas there are only single specimens for most

| |

| − | other species. Among herbivorous dinosaurs, the

| |

| − | large hadrosaurid Saurolophus angustirostris is as common

| |

| − | as T. baatar, whereas other species are rare. Another

| |

| − | striking feature of the dinosaur assemblage of

| |

| − | the Nemegt Formation is the lack of neoceratopsians,

| |

| − | although their primitive representatives (Protoceratopsidae)

| |

| − | occurred in the older Barun Goyot and Djadokhta

| |

| − | formations. In contrast, the advanced neo-

| |

| − | ceratopsians of the Ceratopsidae are common in contemporaneous

| |

| − | North American strata.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Orlov Museum 518

| |

| − | The Mesozoic hall is divided into main space and

| |

| − | upper gallery. The hall is decorated with monumental

| |

| − | color murals about Mesozoic life, and the gallery is

| |

| − | decorated with bas-relief. The largest specimen in the

| |

| − | hall is the cast of Diplodocus presented by the United

| |

| − | States, but most of the exposition comprises specimens

| |

| − | from Mongolia and Middle Asia. Among these

| |

| − | are skeletons of the iguanodontid Probactrosaurus, the

| |

| − | hadrosaurs Corythosaurus, Arstanosaurus, and Saurolophus,

| |

| − | | |

| − | Paleontological Museum of the

| |

| − | Mongolian Academy of Sciences,

| |

| − | Ulaan Baatar 556

| |

| − | and skeletons

| |

| − | of hadrosaur and protoceratopsian embryos and

| |

| − | hatchlings, Gallimimus, Protoceratops, Psittacosaurus,

| |

| − | Saichania, and Saurolophus.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Polish–Mongolian

| |

| − | Paleontological Expeditions 605

| |

| − | The 1965 expedition (23 participants) was one of

| |

| − | the largest. Most of the time the expedition team

| |

| − | worked in two groups. Nine people spent a month

| |

| − | at Bayn Dzak, discovering some new sites with small

| |

| − | vertebrates and significantly augmenting the mammal

| |

| − | and lizard collection. Dinosaur skeletons, including

| |

| − | Protceratops and Pinacosaurus juveniles, numerous

| |

| − | dinosaur eggs and nests, tortoises, and a previously

| |

| − | unknown, small crocodile (Gobiosuchus) were also

| |

| − | found. The second, larger group (14 people) worked

| |

| − | in the Nemegt Basin, mainly at Altan Ula IV and

| |

| − | Nemegt, but also visited Altan Ula III and Tsagan

| |

| − | Khushu localities. Numerous skeletons of dinosaurs,

| |

| − | tortoises, and crocodiles were found, as well as fish

| |

| − | remains, ostracodes, tree trunks, and charophyte oogonia.

| |

| − | Except for numerous Tarbosaurus and Saurolophus

| |

| − | skeletons previously found by the Soviet Expeditions,

| |

| − | the dinosaur skeletons collected represented

| |

| − | new taxa of ornithomimids, sauropods, and pachycephalosaurids.

| |

| − | In the middle of July, the Bayn Dzak

| |

| − | group joined the Nemegt team for several days and

| |

| − | then headed toward the Lakes Valley in the west of

| |

| − | Mongolia to look at Tertiary deposits.

| |

| − | After completion of the expedition of 1965, fieldwork

| |

| − | in Mongolia was suspended for 1 year. In 1967

| |

| − | and each of the successive three years, a group of

| |

| − | five Polish and Mongolian paleontologists stayed for

| |

| − | several weeks in the Bayn Dzak region to search for

| |

| − | small Late Cretaceous vertebrates but no excavations

| |

| − | were undertaken.

| |

| − | The 1970 expedition was also a larger one and

| |

| − | included 15 participants. At the beginning, the entire

| |

| − | team worked at Bayn Dzak, enlarging the mammal

| |

| − | and lizard collection but also investigating outcrops

| |

| − | in the vicinity. When the camp at Bayn Dzak was

| |

| − | closed, the expedition headed south to the Nemegt

| |

| − | Basin. The main camp was set up at Nemegt (Northern

| |

| − | Sayr). The outcrops at Altan Ula II and III and

| |

| − | the Shiregin Gashun (� Shiregeen Gashoon) Basin

| |

| − | north of the Nemegt range were also visited. In addition

| |

| − | to several Tarbosaurus and Saurolophus skeletons,

| |

| − | oviraptorid and pachycephalosaurid skulls and ornithomimid

| |

| − | and ankylosaurid skeletons were discovered.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Soviet–Mongolian

| |

| − | Paleontological Expeditions 723

| |

| − | the American Expeditions could have done.

| |

| − | The first excavations of 1948 were opened up in

| |

| − | the southeastern Gobi at a locality called Sayn Shand.

| |

| − | Here, several skeletons of the new ankylosaurid Talarurus

| |

| − | plicatospineous and fragmentary material of Talarurus

| |

| − | disparoserratus were recovered from the Upper

| |

| − | Cretaceous strata. The expedition then turned westward

| |

| − | to Bayn Dzak, where the Central Asiatic Expeditions

| |

| − | had made dramatic discoveries in the 1920s. As

| |

| − | the Americans had found a quarter century before,

| |

| − | the Soviets found abundant Protoceratops skeletons

| |

| − | and dinosaur eggs. Additional finds included a wellpreserved

| |

| − | large ankylosaurid, Syrmosaurus vimicaudus

| |

| − | (a junior synonym of Pinacosaurus grangeri).

| |

| − | As the Soviet team moved south toward the border

| |

| − | with China, they came upon a broad depression surrounded

| |

| − | by an expanse of trackless, shifting desert.

| |

| − | The Nemegt Valley extends 180 km east to west, and

| |

| − | up to 70 km north to south. Within the confines of this

| |

| − | isolated area the crew located numerous Cretaceous

| |

| − | ‘‘dinosaur cemeteries’’ scattered across the valley

| |

| − | floor. These deposits included hadrosaurs, carnosaurs,

| |

| − | sauropods, ankylosaurs, and ornithomimids.

| |

| − | Among the inhospitable gorges of red sandstone the

| |